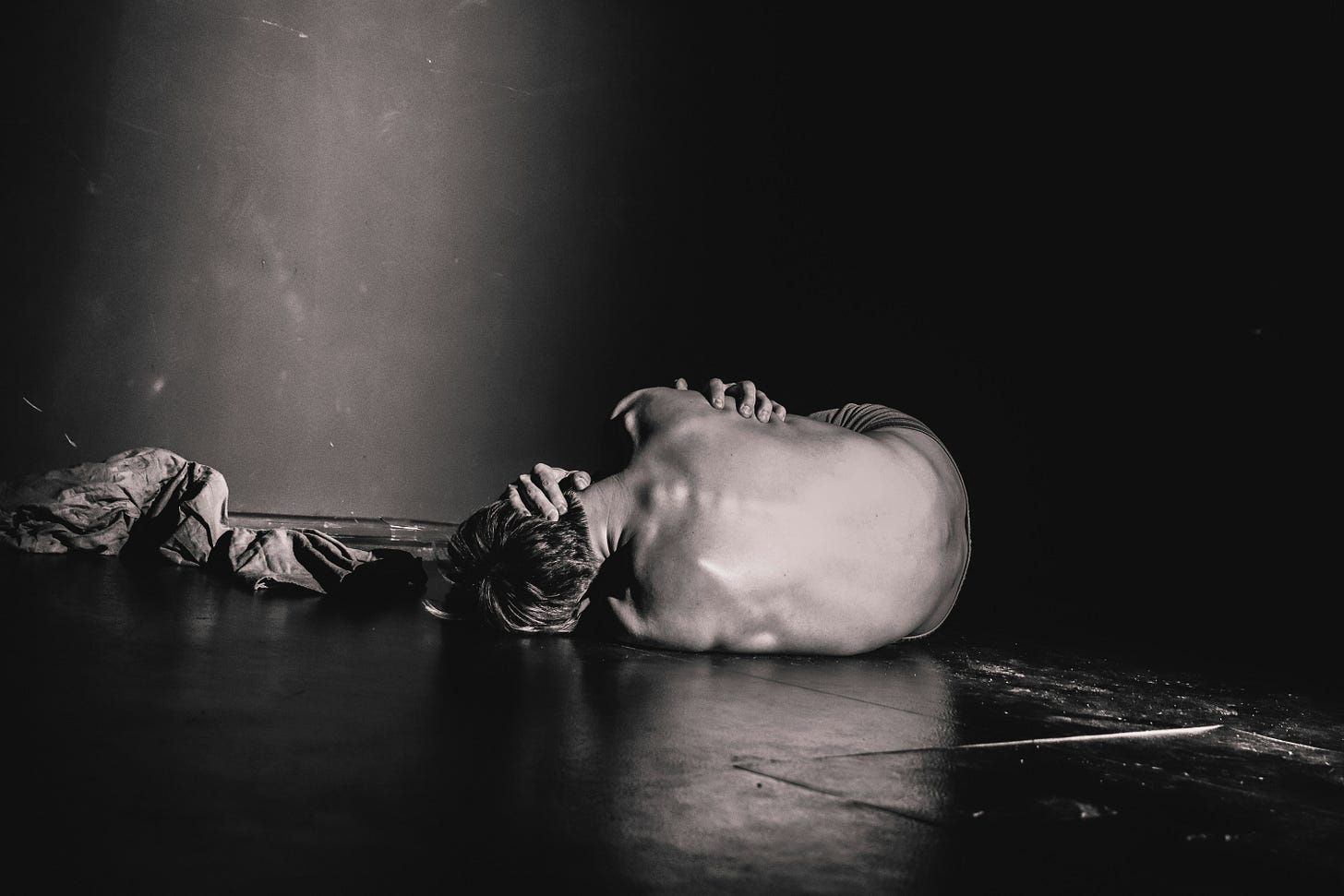

If God Is Good, Why Is There So Much Suffering?

Wrestling with pain, faith, and the hope that is promised to us.

This is part of a weekly Sunday series called The Questions We All Carry: In Search of God, Truth, Beauty, and Meaning. To ask a question, just reply to this email.

It’s the question that won’t go away.

We hear it in hospital waiting rooms, in the wake of tragedy, after funerals, and in dark bedrooms when sleep won’t come. We ask it when the news reminds us of the world’s brokenness, when our prayers seem to go unanswered, or when life takes a painful, unexpected turn.

If God is good, why is there so much suffering? In a world that He created and called “good,” why does it hurt so deeply — and for so many?

This isn’t a question for armchair theologians or ivory towers. It’s the kind of question we ask with grief in our hearts, or fists in the air. It’s raw. It’s honest. It's painfully common. And at some point, it comes for us all.

The man Job, whose charmed life was decimated by a fatal attack on his ten children, his property, his livelihood, and his marriage, said, “When a scourge brings sudden death, [God] mocks the despair of the innocent” (Job 9:23). It’s one of the Bible’s most gut-wrenching lines — anguish speaking without any filter, asking how a just God can allow the innocent to suffer.

Job’s wife was even more direct in her protest. As she sees her husband sit in ashes, covered in painful sores, she says to him: “Do you still hold fast your integrity? Curse God and die” (Job 2:9).

Even Jesus didn’t hold back.

On the cross, as he bore the weight of the world’s sin and sorrow, Jesus cried out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” That cry gives us permission to ask our own hard questions, too. And it reminds us that God is not indifferent to our suffering. Instead, He has entered it himself.

For many, the reality and diversity of pain in the world feels like the greatest argument against the existence of a good God. How can a loving God allow children to starve, wars to rage, or disease to take the lives of people who prayed for healing? How can that same God allow generous, kindhearted people to suffer and selfish, mean-spirited people to live in relative ease?

The late historian and atheist-turned-Christian, C.S. Lewis, once grappled with this very dilemma. In The Problem of Pain, he gave voice to the hurting skeptic’s cry:

“If God were good, He would wish to make His creatures perfectly happy… If God were almighty, He would be able to do what He wished. But the creatures are not happy. Therefore God lacks either goodness, or power, or both.”

At least, that’s how the argument often goes. But Lewis didn’t stop there. Over time, his perspective changed — not by dismissing the pain, but by seeing it through the lens of a Savior who, by His own choice, suffered egregiously.

There’s a mystery to this, to be sure. Christianity never offers an easy answer to the problem of pain. But it does offer something unique. While other worldviews might say suffering is illusion (Buddhism), the result of bad karma (Hinduism), or just the way things are in a capricious, godless universe (atheism), Christianity says something startling:

God suffers with us and for us.

When my daughters were little, one of them broke her arm falling off a bike. We rushed to the ER, where she had to endure the pain of the reset. I remember her looking up at me through tears and the grip of fear, asking why I would let the doctor hurt her more. She couldn’t understand why the very people meant to help her were causing more pain. And to her, I was complicit — I brought her there.

In that moment, I would have given anything to take the pain from her. I would’ve gladly traded places. But I also knew what she didn’t yet understand — that short term pain, paradoxically, was a necessary part of her long term healing. The bone had to be set right before it could grow strong again. There was no other way.

God, it seems, is a parent like that. He takes no pleasure in our pain. But neither does He waste it. In ways we may not yet grasp, He allows the pain He hates to accomplish the healing He intends.

Scripture tells the story of a world made good — very good. No pain. No death. No betrayal. Just beauty, peace, and unbroken communion with God and each other. But then, sin entered the world. And with it came sorrow, decay, and death. The pain we experience now is not part of the original design. It’s an intrusion on the world as it’s meant to be.

This publication is freely available to all and sustained through reader support.

If you wish to support Scott Sauls Weekly and receive bonus content:

But the Christian story doesn’t stop with brokenness. It points us toward a sweeping, cosmic redemption. One day, God promises to make all things new — no more tears, no more suffering, no more death (Revelation 21:4).

The arc of God’s story bends, unstoppably, toward restoration and renewal. But that doesn’t minimize our pain in the present. But it does mean that suffering isn’t the end of the story.

The cross proves this.

What looked like history’s greatest tragedy — the evil, cruel, unjust execution of the Son of God — became the very means of salvation for the world. If God can redeem that, He can redeem anything.

Until that final renewal, we live in the tension between a good God and a groaning world. So what does that mean for us practically?

Faith isn’t about having all the answers — it’s about trusting the One who does. It’s not about escaping pain at all costs. It’s about leaning on the One who walks with us through it. He doesn’t always give explanations, but He always gives Himself. And in the end, we will realize that all along, that’s been the greatest gift of all.

The Apostle Paul, no stranger to suffering himself, once wrote:

“We are afflicted in every way, but not crushed… struck down, but not destroyed… always carrying in the body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be manifested in our bodies” (2 Corinthians 4:8–10).

Suffering is real, and it hurts. But it won’t last forever. Future resurrection is just as real as present day suffering — and it will last forever.

One of the most delicious things you can put in your mouth is a slice of homemade banana bread. But what many people don’t realize is that the key ingredient isn’t a fresh banana — it’s a rotten one. The browner, mushier, and slimier the banana, the better the bread turns out. Without that seemingly ruined ingredient, the bread won’t have the same richness, moisture, or flavor.

It’s a strange paradox, but one that mirrors how God often works in our lives. In banana bread — and in life — the most rotten things can become essential ingredients in God’s plan to work all things together for good (Romans 8:28). In God’s hands, the spoiled and painful parts of our stories can become the very things that nourish others and shape us into something more whole than we were before.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean we should slap a smile on grief or put it all in the “everything happens for a reason” bucket, especially in the moment of crisis and loss. Jesus wept at Lazarus’ tomb. Paul despaired of life itself. Mercy and empathy are an essential part of the grieving process.

Lament is not a failure of faith — it’s part of it. You don't experience grief because there's something wrong with you. You experience grief because there's something right with you. If you don't believe me on this, then I challenge you to read through the Psalms, where David, the “man after God’s own heart,” pours out his anguish to God liberally and often.

But as David’s Psalms also demonstrate, even in our lament, we cling to hope and need not lose heart. And we participate in God’s healing work in the world.

Here are a few ways we can do that:

Listen deeply to those who suffer. Instead of offering answers, offer your presence. Sometimes the holiest thing we can do is say, “I’m here. I don’t know why this is happening to you. But I won’t leave you alone in this, and I know God won’t either.”

Pray honestly. God can handle our questions, our anger, our doubts. The Psalms are full of raw prayers that start in anguished confusion and end in surrendered trust.

Help where you can. Our calling is not to solve all suffering but to be faithful in the face of it — whether through generosity, advocacy, compassion, or simply walking alongside someone in their pain.

Remember that resurrection is coming. As my friend Sandra McCracken says in her song, Fools Gold, “If it is not OK, then it is not the end. And this is not OK, so I know this is not the end.”

The journalist Malcolm Muggeridge, who spent much of his life as a skeptic before encountering Christ, once said:

“Everything I have learned in my 75 years… everything that has truly enhanced and enlightened my existence has been through suffering… and not through happiness.”

It’s such a bold thing to say. And not everyone can say it today. But one day, maybe we will. Because in Christ, suffering never has the last word. As C.S. Lewis wrote:

“Heaven will work backwards and turn even our agony into a glory.”

Even when we can't see it, resurrection is already taking root—planted deep in the fertile soil of sorrow.

And though we must first endure the heat of summer, the stripping of fall, and the chill of winter, spring is coming—once, for all, and forever.

Releasing This Week:

Companion Teaching Videos

The following videos will release this week, expanding on this essay's themes.

Releasing Monday, May 26: Why Does God Allow Suffering?

Releasing Thursday, May 29: Is Pain Part Of God’s Plan?

This is a well written article that is persuasively presented.

Christian theologians have been trying to make sense of this thorny problem for hundreds of years.

How do you solve this seeming impossible contradiction: God is love. God is sovereign. Evil exists.

I have my own views on how to handle this contradiction, but it’s not my place to articulate them here.

This thorny problem is not likely to end anytime soon in the Christian community, and will continue to provoke essays, articles, and books, in an effort to resolve this problem.

I can't know the why of any particular person's suffering anymore than anyone else can, but as for the prosperity of the wicked, I have always loved the following great line: if you want to know what God thinks of money, look who he gives it to.